Solipsia did not announce its authority. It did not need to. Order existed because it was enforced, and enforcement had a name long before anyone thought to question it: the Concordant Standard.

It was the realm’s only military force. Not regional. Not symbolic. Not ceremonial. There were no parallel armies, no household guards of consequence, no competing banners. Where the Standard went, Solipsia was already assumed to be present.

The name referred to two things at once: the banner under which the army marched, and the behavior required to remain within it. To serve was to conform. To fail was to be deemed incompatible. There was no intermediate state.

The Concordant Standard did not recruit by appeal. It did not invoke courage, loyalty, honor, or destiny. Individuals were assessed as material and measured against a fixed operational expectation that did not shift for temperament, ambition, or lineage.

Those who aligned remained. Those who did not were removed. No explanation followed.

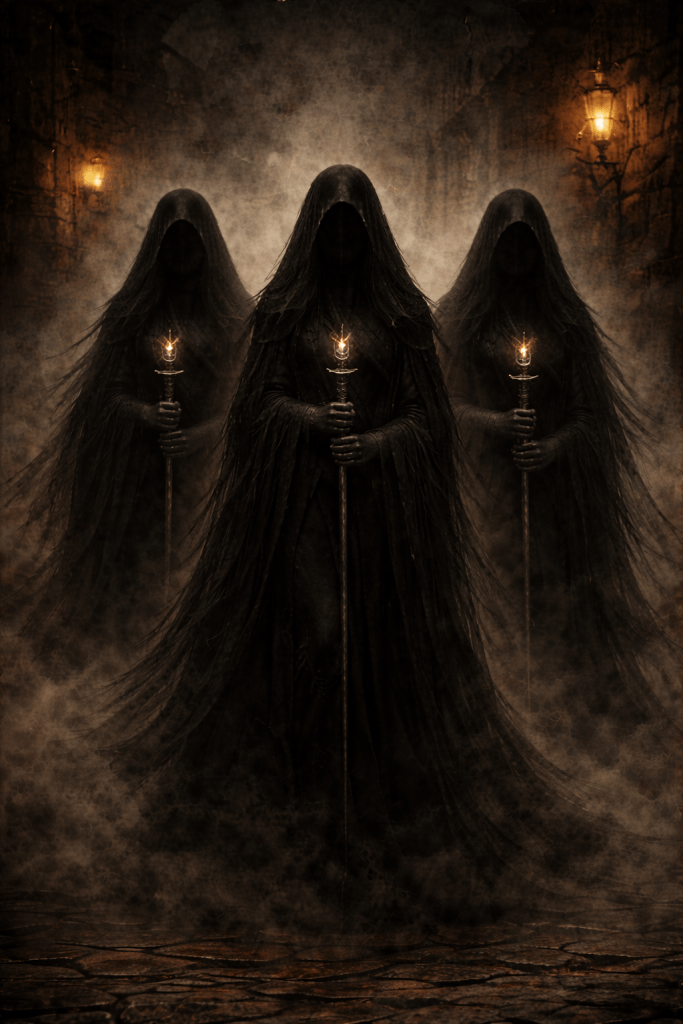

Above the Standard, beyond public record and civic structure, were the Three. They ruled all of Solipsia, though no account could explain how. They had no known names, no recorded faces, no origin that could be traced. They did not appear in public, did not speak through emissaries, and did not justify their authority. Orders descended from them through channels no civilian institution could access, already complete, already final.

There were always three. There had always been three. When one was gone, there were still three.

The Concordant Standard did not swear loyalty to Solipsia itself. It swore concordance to the orders issued from above. Soldiers were not taught who the Three were. They were taught only that orders arrived, orders were sufficient, and orders were obeyed.

Beneath the Standard, at the point where individuals were first tested for compatibility, stood the Forge. It was not an academy. It was not a proving ground. It was not a place of instruction. The Forge was brutal, industrial, impersonal, and final. Its name was intentional. A forge does not teach its subjects. It does not persuade or prepare them. Heat is applied. Pressure is applied. The material either reshapes or fails. Those who required explanation, recognition, or narrative did not survive the process.

Those who understood were reshaped. Those who did not were discarded as unusable material. Failure at the Forge was quiet and procedural. There were no appeals, no records of protest, no ceremony. Once processed out, an individual did not return. The system did not remember what it discarded.

The Forge produced no legends. The Concordant Standard celebrated no heroes. Those who passed became interchangeable. Those who failed became absent. This was the structure that held Solipsia in place.

Civilians struggled to describe them accurately. Not because they had not seen them, but because language failed where expectation usually lived. People said they were quiet, though that was not precise. Silence implied restraint, and restraint implied choice. What the Concordant Standard carried felt more like absence… the absence of noise, hesitation, or emotional weight.

Some said they moved like shadows. Others insisted they moved like machines. The arguments never resolved, because both descriptions felt wrong in isolation. They did not walk with the authority of soldiers, they did not patrol like guards. They passed through, and places were different afterward.

People spoke most often about their sameness.

“You couldn’t tell one from another.”

“I looked twice and realized I’d already seen him.”

“If one turned his head, they all felt like they had.”

Children were the first to stop staring. Adults followed soon after. There was nothing to meet in their gaze, nothing to read or challenge. Looking at them too long felt pointless, even embarrassing , like waiting for an answer from an object. Many civilians reported the same physical sensation: a tightening in the chest, a subtle pressure behind the eyes, a sense that something had already been decided.

They never shouted orders. They never explained themselves. After they left, people compared notes. They realized none of them could recall a voice clearly. No one remembered a face, and no one could describe a single distinguishing feature.What they remembered instead was the after. People lowered their voices for weeks afterward, not out of fear they were being watched, but out of the uncomfortable sense that someone had been listening long before they arrived.

That was how civilians described them. Not as monsters or saviors. But as something that made the world feel less negotiable.

King Robert spoke of the Concordant Standard often. In his younger years he was obsessed with it. He spoke of it so casually, publicly, and without hesitation. In halls, at tables, before courtiers and servants alike, he claimed he had once served beneath its banner. He described it as a past life, a proving ground, something he had endured and survived. He told the story often enough that it became familiar, and familiarity was mistaken for truth.

He told it in front of his sons. They learned early not to question it. They nodded when others nodded. They repeated it when prompted. They absorbed, without comment, that this was how authority functioned: not through alignment, but through insistence. Not through truth, but through repetition. It was sick, though no one named it as such. This was simply the air of Beaverton,a place where the loudest claim hardened into fact if left unchallenged long enough.

The lie traveled. It always does. At some point, no record marks when, the claim reached beyond Beaverton. Whether it reached the Concordant Standard directly, or passed first through other channels, was never established. What is known is only this:

The Beaver King was missing for the better part of an evening. No alarm was raised, no guards were summoned, and no explanation was offered.

When he returned the next day, he bore no marks of injury. His crown sat straight. His robes were unwrinkled. To an untrained eye, nothing had happened. But those closest to him noticed immediately that something had. For weeks afterward, he startled at sounds that had never troubled him before. He slept poorly. He avoided being alone. He began asking questions that made no sense, about who had been in the halls, who had spoken to whom, who had overheard what. He lingered near doors. He watched corners. He flinched when addressed unexpectedly. Most telling of all, he stopped telling the story. The lie vanished overnight, as though it had never existed.

He never again claimed to have served the Concordant Standard. He never spoke of it in the first person. He never framed it as memory or experience. When its name arose, his responses were careful, distant, reverent in a way that bordered on fear.

Whatever occurred during that missing evening had not been violent. Violence he understood. This was something else. He had been seen, measured without argument, without anger, without need to persuade. He had been held in place by something that did not care who he thought he was, only what he was capable of being. And he had failed. From that point forward, his fixation turned outward. The Concordant Standard became something to be admired from a distance. Something to be invoked. Something to be projected onto others. Most notably, onto his sons.He pressed them toward it with an urgency that bordered on obsession. He spoke of duty, of legacy, of what it meant to be worthy, always careful to frame the Standard as an achievement they could reach, though he never had.

Because he knew.

He knew, with a certainty that never left him, that he was not Standard material. He was weak, he was ineffective. He required attention, validation, narrative. The Concordant Standard does not accept such things. So he did what men like him always do when confronted with an institution that will not bend: he attempted to live through others. He pushed his sons toward alignment he could not achieve himself, not out of belief in them, but out of resentment toward the thing that had looked at him clearly and found him unusable.

He never spoke of that night. He did not need to. His fear lingered long after his lie was gone. And the Concordant Standard remained, as it always had, silent, uninterested, and entirely unconcerned with his fantasies.

Leave a comment