Sarmara of Spencer Vale lived along the bank of the Berth River where it runs thin and cold toward the northeast of Beaverton. The Vale there was not a village so much as an accumulation—lean-tos, half-collapsed shelters, scavenged wood pressed into shapes meant to keep rain out longer than they kept dignity intact. Her own dwelling was a lattice of sticks and borrowed canvas, weighted with stones and patience. Poverty was not an event in Spencer Vale. It was the condition—unchanging, austere, and uninterested in mercy.

She was young when Little Lord Brentin first noticed her—barely beyond childhood, though old enough by law to exist without scrutiny. She was tall, spare, and pale in the way hunger encourages. Her blond hair was cut to a practical length, bangs trimmed unevenly. She wore wire-framed glasses that had already lived another life before reaching her. Her eyes were bright blue. Her face was slender and generic, forgettable in the way that makes a person easy to use without remembering.

They met at the Berthlight Dance, one she was fortunate enough to attend at all. Accounts cannot recall why she was there, only that she arrived alone.

The dance was held by the river that night, where the Berth slid over stones with a sound like quiet breathing. Candles lined the perimeter in shallow glass cups, their flames bending in the night air. Lanterns hung from poles and low branches, casting uneven halos of light across packed earth and moving feet. Music had been borrowed rather than commissioned—the parish organ wheezing beneath a canvas awning, a lute plucked steadily beside it. Wax melted. Water moved. Voices stayed low. It was, by all accounts, a lovely night.

They were taken with each other immediately. A First Glow, as the folk called it—an early closeness born of shared light and borrowed music, mistaken for something lasting simply because it felt warm.

They were constantly together after that.

As their relationship settled into habit, Brentin proved himself very much his father’s son. He possessed the same instinct for vulnerability, the same ability to locate it and apply pressure without leaving visible marks. Sarmara suffered from bouts of melancholia—not sadness alone, but heaviness. A dulling of thought. A sense that effort itself was suspect. She kept its causes private, though no great inference was required. Poverty teaches a person to live in an interior landscape, where hope must justify its own existence.

Brentin did not offer comfort. He observed.

He belittled her in increments small enough to be defended. He corrected her speech. He questioned her judgment. He framed his cruelty as clarity and his impatience as honesty. When she faltered, he sighed—not in anger, but disappointment. Over time, she learned to preempt his displeasure, to shrink her needs, to doubt her perceptions before voicing them aloud.

He loved the power of it. The sensation of elevation. The way her smallness seemed to confirm his importance. Making her feel lesser reassured him that he was not.

No guidance intervened. The Beaver King offered no correction. The Queen Consort had long since retreated into silence. The Dowager Queen had modeled domination openly and without consequence. Brentin did not invent despotism. He inherited it, refined it, and found it pleasing.

What followed is uncertain in the public record, as private matters were rarely preserved with precision. It is noted only that Sarmara’s melancholia deepened. On a night later described as fateful, the weight she carried overtook what balance remained. Words were spoken—likely cruel, likely exact. There were other pressures as well: hunger, exhaustion, isolation, the slow accumulation of despair that comes from believing one’s suffering is both justified and unnoticed.

She broke. She attempted to end her own life.

By custom and discretion, the record does not reproduce the particulars of her attempt. The method is referenced only obliquely and is not repeated here. Solipsian chroniclers have long held that the mechanics of despair do not advance understanding, and that such details, once written, tend to outlive the lesson they were meant to serve. The entry is therefore closed on the fact alone: that an attempt was made.

She did not succeed.

And here, by any reasonable measure, tenderness might have entered. Care. Restraint. Even silence.

Brentin chose none of these.

He told her she was weak.

He told her she was stupid.

He told her he wanted nothing to do with her.

He expelled her as one removes an inconvenience. No comfort. No escort. No concern for whether she would make it back at all. He cast her out and closed the door behind her.

The walk back to Spencer Vale was long in a way that defied distance.

At first, Sarmara moved quickly, driven by the shallow urgency of flight, as though speed alone might outrun what had been said to her. But the road did not shorten, and the night did not thin. Her breath came uneven, catching in her chest where panic and exhaustion argued for control. The ground beneath her feet felt unreliable—stones shifting, roots rising unexpectedly, each step demanding more attention than she could comfortably give.

Thought began to fragment.

She replayed his words not as sentences, but as conclusions, weak, stupid, unwanted, each one landing with the dull certainty of truth rather than accusation. There was no counterargument left in her. No inner voice rising to defend herself. Even the instinct to protest felt indulgent, something meant for people whose suffering might be negotiable.

Her body lagged behind her mind. Legs burned. Ankles wavered. At one point she stopped without intending to, simply standing in the dark, unsure how long she had been motionless. The river could be heard in the distance, steady and indifferent, continuing its work without regard for who reached its bank or failed to.

She wondered, briefly and without drama, whether stopping entirely would change anything.

The thought did not frighten her. That frightened her more.

When she resumed walking, it was not with hope, but obligation—the dull knowledge that the road did not care whether she wished to be on it. Each step felt less like progress and more like compliance. Existing because she had not yet been granted permission to stop.

By the time the Vale came into view, dawn was beginning to dilute the dark. The light was thin and colorless, offering no comfort. Her shelter waited where it always had, unchanged and unimpressed by her return. Sticks. Canvas. Silence.

She reached it and sat for a long while before entering, hands resting uselessly in her lap, as though waiting for instruction that never arrived. The despair did not leave her there. It simply settled, quiet, and patient, certain that it would be given time.

A few days passed.

Little Lord Brentin was unmoved by the passage of time, already turning his attention elsewhere, as was his habit. He did not tolerate solitude well. Being alone required reflection, and reflection had never served him. So he moved on to his next interest, as though the matter of Sarmara had concluded itself.

In those days, Little Lord Brentin The Beneficiary and Baylor The Bound were still barely men and yet already deeply entangled. They had been thick as thieves in their youth, Baylor still bound, still pliable, and Brentin already sharpening into something harder. One evening, over too many ales, Brentin spoke of the separation as though it were an inconvenience resolved. He did not call it cruelty. He did not call it abandonment. Whatever Solipsia names such endings, he treated it lightly.

As the drink took hold, Brentin proposed a wager. It was casual. Careless. Spoken as if no person stood at the center of it.

Baylor, unsteady and unthinking, and properly soused, agreed.

The terms were simple and grotesque: that Baylor could not go to Spencer Vale and persuade Sarmara to receive him that very night. It was framed as bravado, as proof of charm, as nothing more than a boyish test of nerve. Brentin did not mention her recent collapse. He did not mention her fragility. As though betting her body were acceptable even under the best of circumstances, which it was not.

Baylor went. How he made it there as much ale he had consumed is a question no one can answer. He found her where Lord Brentin had left her, alone, diminished, and still carrying the weight of what had been done to her. She was sullen, exhausted, and unguarded in the way grief often leaves a person. Baylor brought sweet wine. He spoke gently. He leaned into her sadness rather than away from it. What little resistance remained was no match for attention framed as care.

He found it easy. Too easy.

Baylor returned at the hour of the Owl, unsteady on his feet, barely making it back to collect what he had been promised. The payment was trivial, something small and absurdly insignificant for the harm it represented. A few coins. A favor. A token hardly worth remembering.

Brentin paid without comment.

And in the ledgers of Solipsia, the matter passed without remark; another private wrong folded into silence, carried by the person least equipped to bear it.

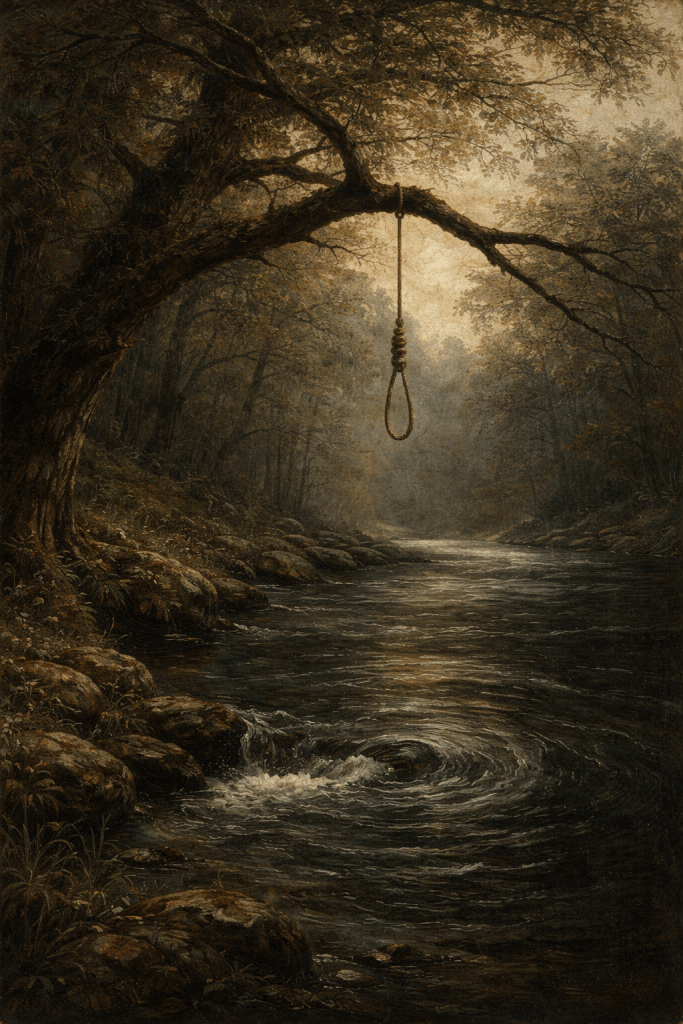

Neither of them thought of it again for several days. Not with cruelty, worse than that, with absence. The Reckoning arrived by notice, entered into the Grand Scroll, carried with seal and citation. Spencer Vale found her at first light, suspended from a low branch over the Berth where the undertow ran strongest. The river kept moving. The branch was cut back. The body was taken down.

Spencer Vale mourned without excess. Fires burned lower. Work slowed. The riverbank was avoided for a time. Her name was spoken carefully, if at all, but with weight.

Only then did the news reach those who had last touched her life and walked away believing it finished.

Brentin absorbed it without visible reaction. Not denial. Not shock. Adjustment. The absence where response should have been was complete.

Baylor the Bound felt it. He went to the gathering held in her name. Her family’s custom was observed. They burned the body as they always had, smoke lifting pale and straight into the air, ash returned to water and soil. There was no sermon worth recording—only the quiet presence of those who knew what had been lost and what could not be repaired.

The scar it left on Baylor did not fade. It followed him through years and titles, through bindings and unbindings, into the man he would one day become. He learned there, too late and at terrible cost, that harm can be done without hatred, that silence can wound as deeply as intention, and that being less cruel is not the same as being good.

He vowed once, and without witness—that he would never again be the reason someone felt so diminished that leaving the world seemed reasonable.

Even so, he had a long way to go before becoming Baylor the Brave.

This was not redemption. It was a notch. Another weight added to the slow accumulation of conscience. It made him careful. Watchful. Willing to stand beside rather than above. In Solipsian reckoning, such growth rarely announces itself. It accrues.

The record further warns that Drucelia should be deeply, urgently concerned.

Sarmara. Mysty the Gleaner. Others whose names do not survive intact. The pattern is neither subtle nor concluded. It is likely ongoing. Drucelia’s proximity has dulled her alarm. Familiarity has disguised danger as devotion. And Brentin, far from softening with age, has sharpened.

Worse still is his alignment with the Beaver King. Together they form a closed circuit, one modeling cruelty, the other refining it. In such arrangements, harm does not merely persist; it normalizes itself.

If Drucelia were able to see the full record clearly, she would leave.

That she does not is explained, if not excused. Her appearance, unkempt hair, poorly tended; teeth crooked and heavy with tartar from long neglect, no true talent to speak of, and very quick to run on emotion has limited her perceived value in a society where beauty functions as permission. She has learned to expect little, and so accepts what should never be accepted.

This, too, is cruelty, what the world withholds until endurance feels like the only option.

The record closes with clarity.

This trait was not learned late nor imposed accidentally. It was borne into him and reinforced wherever it sought confirmation. Sarmara revealed it. Mysty confirmed it. Others merely sustained it. Whinyth alone disrupted it, an angelic interruption that forced him, briefly, to consider another self he might have become. And when that moment arrived, when choice was no longer theoretical, he chose the Beaver Faction.

He chose inheritance over interruption.

Power over mercy.

Dominion over love.

The presence of Whinyth proves redemption was offered. His rejection of it proves there is none forthcoming.

The record ends not in grief, but in certainty:

There is no hope.

Leave a comment