Before King Robert learned to lie, before cruelty was excused as “temper,” before the kingdom learned to look away… there was Brynda. Not merely a bad woman, a negligent mother, but a patient cultivator of rot.

If the Devil works hard, Brynda works harder— because she doesn’t rush. She waits.

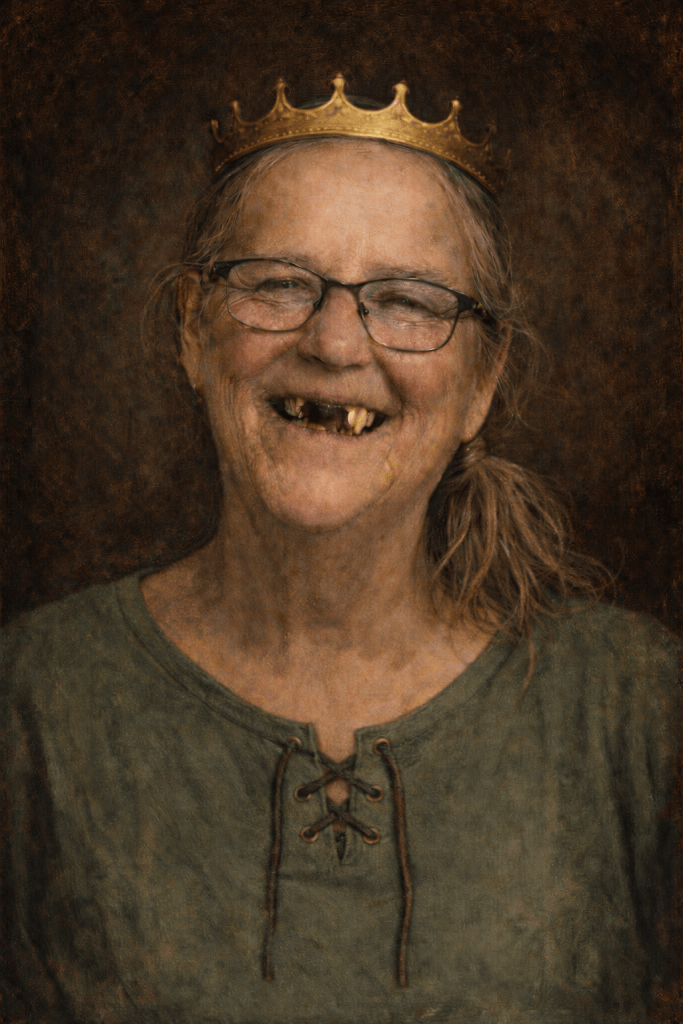

The now Dowager Queen Brynda is in her early seventies—a hard seventy, worn without grace or apology. Her hair is thin and stringy, gone gray with hints of dingy yellow, hanging as though upkeep was long ago deemed unnecessary. Her face is wide and deeply pruned with age, the features large and blunt, offering no softness for the eye to rest upon. Thick glasses sit heavily on her nose, magnifying eyes that squint not from frailty, but from suspicion. They do not wander. They measure.

Her hands are unmistakably mannish—broad, veined, blunt at the knuckles—hands built to grip rather than comfort. She dresses simply and without variation: long denim skirts without exception, paired with plain tops that suggest neither humility nor modesty, only indifference. This uniform has not changed in decades. It is not restraint. It is refusal.

Her most identifying feature is her neglect—nowhere more apparent than in her teeth. Along the bottom row, the front teeth remain, square and widely spaced, roughened by years of decay. Above them, most of the top teeth have rotted away, save for a single prominent survivor on the left side—dark, stubborn, unmistakable. It lingers in memory not because it is shocking, but because it is unaddressed.

Brynda is as ugly on the outside as one might expect—but it would be a mistake to think this is the affliction. It is merely the evidence.

Unlike Auntie Carrow whose deformity worsened in proportion to the harm she sowed, Brynda required no transformation. She was not warped by consequence. She was born this way. Large. Hard. Unsoftened. Only refined.

Brynda was the youngest daughter and second-youngest child among six born to her mother’s first marriage. Her mother, Irenna, was a salt-of-the-earth woman from the base of the Vireholt mountains—poor, decent, and raised right.

Her first husband, Ornery, was a raging alcoholic. They met on the mountains before drink hollowed him out and violence followed. After six children, the family moved closer to the capital and settled in StoneWake.

It was there that Ornery abandoned them.

Word later traveled that he fled to Belmarche with another woman and began an entirely new family. He never returned. He never saw his children again. In time, neither he nor that second family were seen again at all.

Brynda was very young. Whatever pain existed then belonged to others. What she inherited was absence, silence, and a mother already exhausted.

Irenna buckled down. She raised her children and later married Matthis TaylorBlack, a capable, even-tempered man who built wagons and sold candied apples from the front of his sod house. He brought six children of his own into the household. From that union, Montrec TaylorBlack was born.

Matthis was an okay man. Not cruel. Not clever. He believed work and structure would correct what attention did not. Together, Irenna and Matthis built what would become the Beaverton Kingdom.

What they built was solid. What followed was not of their careful making.

By nearly all accounts, Brynda was the least favored child. Not because Irenna was unloving, but because Brynda was difficult to love. She was unpleasant to look upon, sharp-tongued, resistant to correction. Knowing she was least favored only made her act out more.

As she entered adolescence, her fixation on attention intensified. Irenna could not leave her unattended. Brynda was pulled from schooling early and kept close—not as punishment, but necessity.

During this period, Brynda was gravely wronged by boys from StoneWake. What mattered was not the event, as This Minstrelle will not sing that song, but the aftermath.

Confusion replaced clarity. Pain tangled with blame. Whatever had been taken from her would not be restored—and worse, it would now be counted against her. Shame entered the house. In StoneWake—and most of Solipsia with the exception of the less inhibitive Solmere—dishonor did not follow those who caused harm. It settled on households. On mothers. On daughters. It was not right. It was the order of things.

What might have healed instead hardened. What hardened was not resolve, or strength, or wisdom. It was closure. Something in Brynda shut rather than healed. Pain did not turn inward and become reflection; it turned outward and became expectation. She did not ask why harm followed her. She accepted that it did, and quietly concluded that this made her exceptional. The world, to her mind, was not unjust—it was confirming something she had always suspected: that she was different, marked, entitled to behave as others could not.

From that point on, Brynda stopped reaching for repair, she began reaching for permission. When no permission was granted, she took it anyway.

Most people possess some natural gift. Our Brynda did not—except one. She was ignorant. Superstitious. She believed every wives’ tale she heard. She mistook coincidence for omen and rumor for truth. But she possessed narcissism in abundance.

Not confidence—certainty. The belief that whatever she felt must be true, and whatever she wanted must be justified. It insulated her from doubt and excused every appetite. She did not manipulate with intelligence, she manipulated with conviction.

By the time she was nearly grown, Brynda met Roderic of ArthurAlley.

ArthurAlley lay on the sewage-runoff side of Vireholt—a place of foul water and generational poverty. Roderic grew up angry, uneducated, and mean. Evil recognizes its own. Roderic drank heavily and often. He cared only for his pipes and his ale. Brynda was drawn to the collapse of restraint—the volatility, the intensity, the familiarity of it.

Their union was explosive. Arguments were public. Reconciliations unbelievable. No one could understand why they married—except that chaos felt like home to her.

Provocation and Appetite

Marriage did not civilize them. It gave Brynda a stage. Roderic drank just fine on his own, but Brynda learned how to accelerate it. She poured for him. Refreshed his cup. Encouraged excess with feigned indulgence and false concern. She knew exactly when to keep him drinking and when to pull back—long enough for resentment to ferment. She did not fear his anger. She cultivated it.

The louder he became, the clearer her role grew. The worse he behaved, the more convincing her performance outside the home would be. Disorder was not a risk—it was a resource. When eruptions came, Brynda endured the aftermath with grim resolve. Suffering became proof…proof that she was wronged, long-suffering, owed.

Roderic was repeatedly taken into custody by officers of the Concordant Standard. Each time, Brynda retrieved him. Each retrieval diminished him. Each retrieval enlarged her.

Addiction to Injury

This was where Brynda learned to savor it. Not merely the sympathy, but the injury itself.

Pain became the gateway to attention. Submission became the path to control. Intimacy fused with degradation until she no longer recognized them as separate.

Outside the home, she curated the aftermath carefully. Endurance became virtue. Bruised dignity became currency. Inside the home, compassion was spent nowhere.

This was not masochism. It was control through injury. Brynda was not merely harmed. She was invested. The pain was not the cost, it was the point. Pain was not merely something Brynda endured or curated—it was the condition under which she felt most real. And like all compulsions left unchecked, it did not remain contained. It spilled outward, attaching itself to whatever followed.

The Children that she was to bear were not planned. They were collateral.

Neither pregnancy came from foresight, desire, or any vision of family. They occurred in the same way everything else in Brynda’s life now occurred, through excess, neglect of consequence, and the mistaken belief that nothing truly applied to her. Motherhood did not interrupt the cycle. It simply absorbed it.

What should have introduced care instead became another arena for possession and deprivation, intensity and absence. The same patterns that governed her marriage reappeared almost immediately, only now with smaller bodies and longer shadows.

By the time the children arrived, Brynda was already practiced at misreading damage as meaning. Motherhood did not change her. It gave her new material.

Motherhood

When Motherhood came, it did not come naturally to Brynda. Her attachments were not nurturing; they were consumptive. She sought intensity, not care. Control, not attunement.

Two children came of this union. First, Robert Ornery From the moment of his birth, Brynda fixed on him with a fervor that unsettled those around her. She did not simply love him; she claimed the babe. Separation was resisted at every stage.

She continued to nurse him at her breast until he was seven years old. This alarmed nearly everyone. Midwives, neighbors, and kin whispered. Some called it indulgence. Others called it perverse. Brynda dismissed them all.

Robert was not taught independence. He was taught belonging—to her.

Two years later came Sister. With her, the bond never formed.

Care was delegated whenever possible. Sister was frequently left to nurse from a goat rather than her mother—a practical decision that hardened into habit. The result was visible: she grew heavy and placid, fed but not held, present but not cherished.

The contrast was unmistakable. Robert was consumed. Sister was managed. Both children bore the consequences.

Robert grew into the certainty of being chosen. Sister grew into the vacancy of being spared. And Brynda, watching both outcomes unfold, mistook possession for love and neglect for efficiency—never questioning why destruction followed her so faithfully.

Now that you understand how Brynda was made, not born of mystery, nor forged by a single moment, but assembled slowly from neglect, indulgence, appetite, and reward— the rest requires no further explanation.

This is her villain origin story. What follows is not history, but consequence. Not analysis, but echo.

And so, having laid the bones bare, This Minstrelle may now sing of her personally—in verses sharper than prose, in melodies that carry what polite language cannot, and in songs where names are remembered even when faces are excused.

Some stories must be told straight. Others must be sung. Brynda has earned every note.

Leave a comment